Fulfilling the Role of the Fourth Estate: The Future of Digital Journalism

The steady, painful decline of Japan’s print journalism is a long-told story of an industry struggling to adapt to changing times. According to the Japan Newspaper Publishers and Editors Association, the total newspaper circulation in Japan has been decreasing over the past decade from 52 million in 2006 to 43 million in 2016, and companies have been facing cuts in funding or even bankruptcies. While the roles of the press as watchdogs, informers, and promoters of public dialogue have been essential in upholding the pillars of democracy, the decline of print journalism has brought its successor—digital journalism—into the spotlight, fueled by the ever-increasing speed of new technological developments. However, the gradual transition to online news begs the question: will digital journalism be able to fulfill the role of the fourth estate, and continue to bring forth debate and analyses of news for the public?

Agora, an online news organization dates back to the early 2000s. This was a period when, its editor-in-chief, Mr. Nitta claimed, online news was divided into two extreme camps: online newspaper sites or anonymous message boards, namely 2channel. Agora was founded in 2009 as an alternative, to provide a “platform for speech” that publishes opinion pieces penned by both politicians and experts in the field. Mr. Nitta said that analyses by experts have a benefit in that they can lead to unexpected revelations; a prime example is when it was reported—first on Agora—that Renho, the leading candidate for leader of the opposition Democratic Party in 2016, had retained her Taiwanese citizenship. Web users gathered further evidence and the scandal ended up becoming a major detriment to her campaign. This, mused Mr. Nitta, reflects the “power of the internet to influence elections,” whereas “traditional mass media have strict restrictions in that area.” Although this in turn gives internet media sites greater responsibility in providing fact-checked pieces, this is in fact another benefit of the web because fact-checking can be done in real-time (as seen in the presidential debates leading up to the U.S. presidential election in the last year, most notably by Politifact), something that is impossible to do in print format.

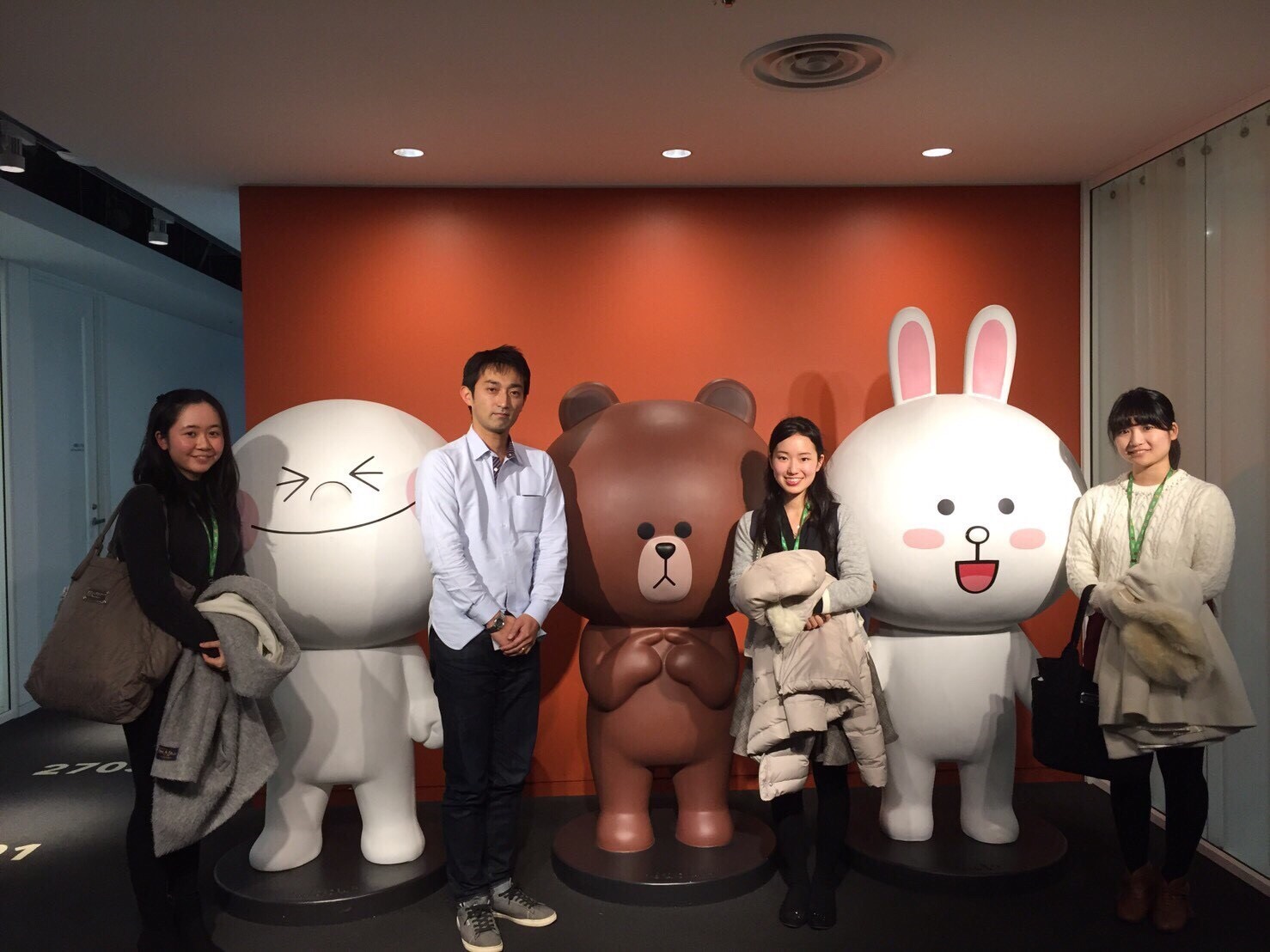

BLOGOS—another online news site run by LINE—has a similar concept to Agora and publishes opinion pieces by over 1,000 bloggers, including experts and politicians. Deputy editor Mr. Masayuki Nagata said that his ultimate goal is to provide readers with a dissection of the news, something that is becoming less frequent in traditional mass media due to resource cuts, which force it to focus on “straight news”. Covering the context behind the headlines is especially important, said Mr. Nagata, because many news readers think they have sufficient knowledge of politics and economics. In reality, however, they do not have enough knowledge to be able to fully interpret the meaning of the news by themselves, a point also emphasized by Mr. Nitta. In fact, Agora’s founder, Nobuo Ikeda, frequently publishes “kids’ version” articles that explain the basics behind questions relevant to the news, such as “is inflation the same as paying tax?” or “what is a tax haven?”, which Mr. Nitta said there is little space for in print journalism.BLOGOS’s other focus is on providing a platform for online discussion. The discussion system, featured prominently on the BLOGOS homepage, poses a question by the editorial team (anything from “should the emperor be allowed to abdicate?” to “what do you think of Obama’s visit to Hiroshima?”) for anyone to freely answer and debate. While Mr. Nagata admitted that it is sometimes difficult to discern between deleting abusive comments and “protecting their freedom of speech,” the site has been uniquely successful in generating hundreds of comments in contrast to print journalism, which publishes only a handful of readers’ voices in the paper.

A major point of concern among online news providers is bringing in revenue. BLOGOS’s main earnings come from advertising, and although Mr. Nagata admits that it would be easy to focus on entertainment articles that bring in the most clicks, he said that there is a growing sense of responsibility among the digital journalism community to provide well-researched and fact-checked articles about political and economical issues to keep the public informed. He also cites Buzzfeed News—which released a Japanese version last year—as one of the “most important sources right now for investigative journalism,” which is in decline in Japan but may be revived, he said, by efforts of online journalists. Mr. Nitta echoes a similar concern, saying that Japan does not have a culture of philanthropy, unlike the United States, and grants for journalism are rare. However, while Agora itself has struggled with bringing in revenue in the past, Mr. Nitta believes the significance that journalism has in society is reason enough to continue doing his job.

Mr. Nitta compares the current state of journalism to the Bakumatsu, comparing traditional print journalism to the declining Tokugawa shogunate and the pioneers of digital journalism to Sakamoto Ryoma, a lone wolf who sought to change the old system and helped bring forth the Meiji Restoration, a new age. However, just as Sakamoto alone was not able to modernize his country, it will take a greater effort on behalf of the entire digital journalism community to design news outlets that are not only fact-checked and accurate but that generate debate and discussion, enhancing the features that have faded from print journalism. Agora and BLOGOS have taken the lead—but if others will follow remains to be seen.

Written by Ayako Morihara, Ryoko Shibata, Rino Shibata

Edited by Takeru Suzuki

I have read the Future of Digital Journalism with some interest. However, Ⅰstill hope that the Mita Campus in a printed form will be published. For that you need articles of more substantial context rather than small stories about the daily Japanese life. n.k.