The Fight for Media Literacy, One Episode at a Time

Since the advent and subsequent boom of social media and internet access in the late 1990s and early 2000s, news has become easier than ever to be shared and spread to the masses. With this great gift however comes with a cost: the power to deceive.

Misinformation in media has existed since as early as 1300 B.C, but the latest developments in communication in the past ten years have made misinformation more widespread than ever.

The barriers to create and share news have never been lower. In order to create news, one need to do nothing more than make a blog or a comment and put on the web for the world to see. Fake news has become a global plague and has eroded people’s trust in the media itself.

While politics aren’t the only topic at hand, in 2019 the Oxford Internet Institute found that over 70 governments and political parties across the world have manipulated public opinion with false information in media outlets. These efforts have doubled in the past two years by researcher’s estimates.

Major internet platforms are the most popular medium for spreading false news. Sites like Twitter, Facebook, YouTube are the largest contributors.

How can we spot fake news and avoid its pitfalls? The answer could be media literacy. As our team began researching about fake news, we ran across Media Times, a television program produced by the NHK focusing on media literacy. Earlier this year our team visited the NHK Broadcasting Center and interviewed Mr. Mitsui, the director of Media Times.

Media Times is an children’s educational program with the goal of developing media literacy for Japanese youths. The show follows the activities of a fictional news company that does research on mass media activities.

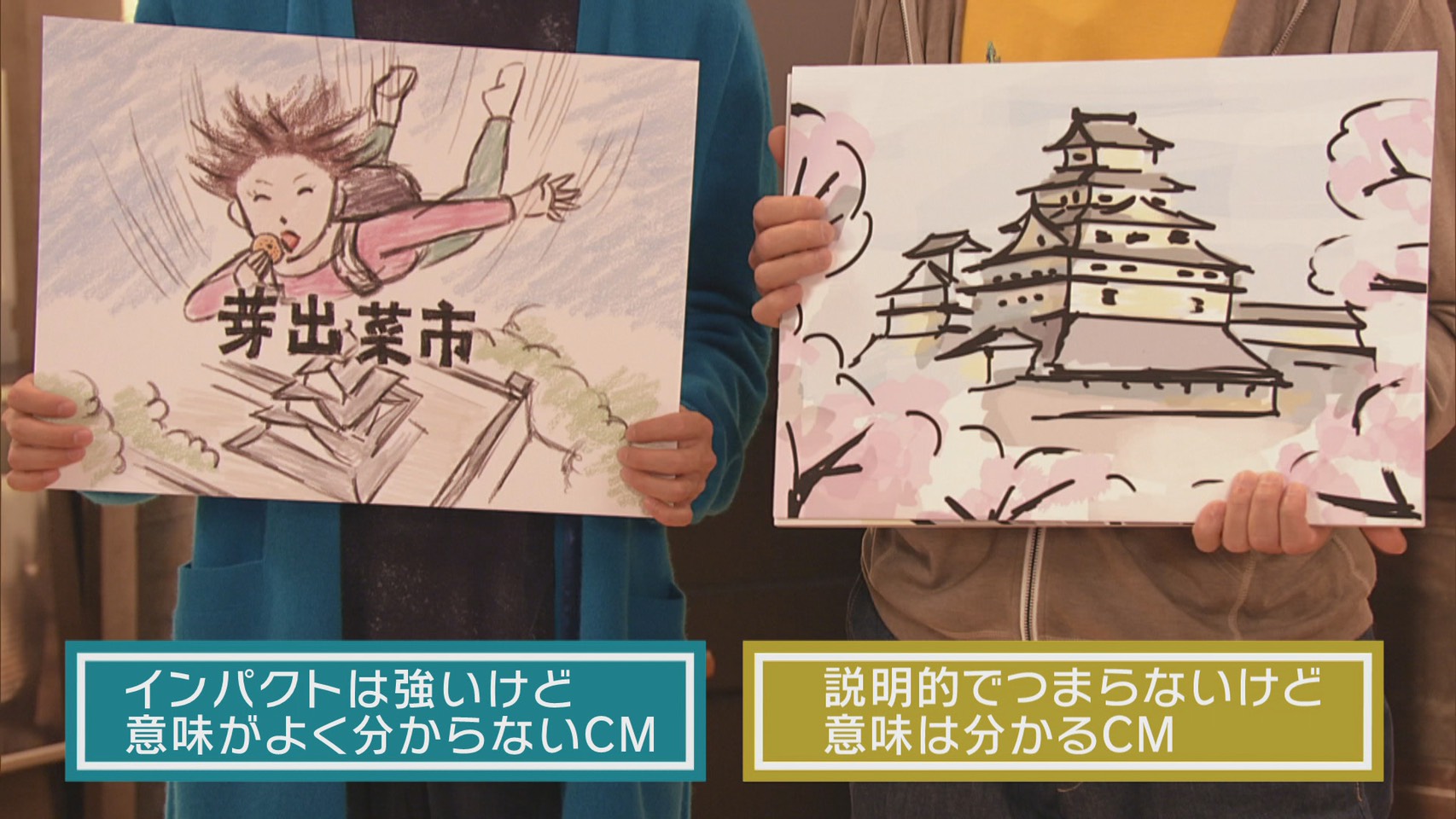

The series consists of 20 ten-minute episodes, in which the main characters introduce an aspect of mass media such as Internet news sites, videography, a fact-checking company, and an advertisement agency. At the end of the story, a character poses a question about what media should be like and encourages viewers to discuss the matter.

Media Times is one of the “NHK for School” television programs, which are designed as educational materials for teachers to use in classroom environments.

Mr. Mitsui has seen how teachers make use of the program and has presented some of their findings at academic conferences such as the Japan Society for Educational Technology. The production team prioritized input from those in the academic community and formed meetings on how to attract the attention of educators and their students.

As a result, from their input, the production team chose to feature popular social media pundits, actors and a band to sing the theme song which has proved to be popular among children and even teachers. All episodes are available for free on their website in conjunction with supplemental materials so that teachers can easily use them in lesson plans.

Typically, the NHK staff produce their “NHK for School” programs following the curriculum guidelines set by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), but Media Times is an exception. This is because the MEXT guidelines do not directly address media literacy. What made the director decide to produce this program knowing that it did not fit within the curriculum? Mr. Mitsui gave us three main reasons.

Firstly, the media landscape has changed drastically in the past ten years. In the past, people typically consumed media through magazines, newspapers, TV and radio, but now the internet, SNS, and video platforms have become accepted media outlets which means the media has become greatly diversified. Furthermore, the previous educational programs of the NHK didn’t address these new forms of media.

Second, there was a change in the curriculum guidelines. With the introduction of “active learning”, encouraging independent and interactive learning at the elementary level in the new curriculum, there was a gaping hole in the older materials. The NHK has produced programs related to media literacy in the past, however these programs were in a documentary format, the program structure focused on the surface level of information acquisition.

Media Times, on the other hand, contains a program structure emphasizing viewer engagement by adopting a TV drama approach to incorporate active learning. This method makes it easier for elementary and junior high school students to discuss, because the issues are clear, and their position is easy to clarify.

Lastly, there was a change in the mindset of the production team. Mr. Mitsui moved to Mito Broadcasting Station in Ibaraki Prefecture after entering the NHK, and in less than one year later, the 2011 Great Eastern Japan Earthquake occurred. While damage to three prefectures in Tohoku, Iwate, Miyagi and Fukushima, had been widely reported daily, damage to Ibaraki Prefecture was scarcely reported, although the tsunami and the Fukushima nuclear accident affected the area.

Media has an unfortunate characteristic of giving priority to the perceived “greatest crisis”, leaving coverage on Ibaraki to languish. Then the tweets came.

Social media posts exaggerated the severity of situation in areas in which supplies were sufficient. Others viewing the posts unknowingly retweeted posts like theses in hopes of helping others, only adding to the confusion. This resulted in an overabundance of supplies in certain shelters, while other shelters were desperately in need of supplies.

According to Mr. Mitsui, “people started to doubt the veracity of the news and felt like media might be hiding something.” Mitsui’s production team was frustrated because they wanted to report the damage in Ibaraki, but given the limited time for news segments, they had to follow the “priority” news stories. People in Ibaraki felt alone and forgotten in the crisis, fueled by a lack of traditional news coverage and false information on social media.

Experiencing the shortcomings of mass media firsthand, the experience motivated the production team to correct course and focus on how people communicate. Mr. Mitsui and the production team thought about the function and structure of sending and receiving information through media, then concluded that media literacy is needed as a “grammar,” common to all consumers of media. Thus, the idea for Media Times came about.

Mr. Mitsui expressed that the mission of Media Times is encouraging discussions of opposing viewpoints, so that children understand the difference in opinions that others around them might have. By mutually expressing their thoughts they can learn how and why people can form differing opinions. “I wonder if this process of trying to understand each other could help solve problems in communication,” stated Mr. Mitsui.

Media literacy is not the perfect panacea for fake news. We live in the society where true and false are easily jumbled and misconstrued, literacy can only get us so far.

Regardless, it is important for us to keep thinking about how information is disseminated in mass media, how we chose to consume it and what it means for the present and future.

Written by Kohei Miyauchi, Toko Sone and Yusuke Kazamaki

Edited by Jacob Wagnon